A KILCULLEN HEROINE. THE CRIMEAN JOURNEY OF SISTER MARY ALOYSIUS DOYLE

A Kilcullen Heroine.

The Crimean Journey of Sister Mary Aloysius Doyle

James Durney

On 10 October 1908 The Kildare Observer noted the death of Kilcullen native and Crimean War heroine, Sister Mary Aloysius Doyle:

The death took place at the Convent of Mercy, Gort, Co. Galway, on Monday, of Sister Mary Aloysius Doyle, last of the band of sixteen Irish nurses who went to the Crimea to assist Miss Florence Nightingale in nursing the wounded soldiers. The deceased religeuse, who belonged to a highly respected family of Old Kilcullen, in this county, had reached the venerable age of 93 years. In 1897 she was presented with the decoration of the Red Cross by the late Queen Victoria, old age preventing her from accepting Her Majesty’s invitation to visit Windsor to receive it.

Sister Mary Aloysius Doyle was born Catherine Doyle in 1819 near Old Kilcullen, Co. Kildare, one of seven children of John and Mary Doyle. She had three sisters and two brothers – James and Nicholas. Nothing is known of her education or early life. On 30 April 1849 Catherine Doyle entered St. Leo’s Convent of Mercy, in Carlow, where she taught at the adjoining school for five years. She also attended to the local poor and to the sick of the town throughout a cholera outbreak. Doyle was professed in December 1851, taking the name Mary Aloysius. Her sister, Margaret, also joined the Sisters of Mercy a decade later, at the Gort Convent. Another sister entered the Loreto Congregation, while the daughters of her youngest sister Elizabeth Hooney, subsequently entered Gort Covent.

In autumn of 1854 Britain, France and Turkey became allies in a conflict against Russia. The main theatre of war was the Crimean Peninsula, on the northern shore of the Black Sea, 295 miles across the sea from the Turkish capital Constantinople (modern day Istanbul) and from the first hospitals of the war at Scutari and Koulai. During the next two years, as generals and politicians bungled and dithered, the soldiers in the trenches before Sevastopol suffered terrible conditions and died in scores in senseless attacks on Russian fortifications. Newspaper reports told of primitive hospitals filled with dead and dying. Trenches were crammed with corpses. The wounded and frost-bitten lay awaiting death with no one to attend them. Food was vile and accommodation rat-ridden and vermin-infested. The only nurses provided by the British army were ‘worn-out pensioners’. Thirty Irish and English nuns answered the appeal which followed a public outcry against the terrible conditions under which thousands were dying at the battlefront for want of proper care.

Florence Nightingale, a young wealthy Englishwoman, was asked by the British government to form a party of nurses, which included five Sisters of Mercy under Mother Clare Moore from Bermondsey, London. The government then decided to organize a second band of nurses and it was in this group that fifteen Irish Sisters of Mercy under Mother Frances Bridgeman arrived in Constantinople in December 1854. These nuns were all volunteers and came from different convents. They were encouraged to keep diaries or journals of their travel to, and experiences in the Crimea. Only three of these journals survive, among them that of Sister M. Aloysius Doyle, A Sister of Mercy’s Memories of the Crimea, published in Dublin, in 1904. In January 1855 Sr. Doyle was among five nuns sent to the General Hospital at Scutari, on the Asian part of Constantinople. In her memoir she gave a simple account of the hardship of their lives and the dreadful conditions under which they had to work in the makeshift hospitals. Sr. Doyle admired Mother Bridgeman and her ability to organize and to get things done. In her journal she refers briefly to the difficulty of dealing with Florence Nightingale and how badly she treated the nuns. However, Sr. Doyle does not dwell too much on this subject and perhaps was not aware of all the intrigue.

Florence Nightingale’s relationship with Sr. Clare Moore and her nuns remained, in general, cordial. However, the second party of nuns had arrived with the nurses of Mary Stanley, Florence Nightingale’s one-time friend, and now nursing rival. The ill-feeling Nightingale felt for Sr. Bridgeman and her nuns was, perhaps, motivated by this association. Bridgeman was also a woman of some experience and was used to being in a position of authority. Nightingale, despite her publicity, was a comparative novice in the field and saw Bridgeman as a potential threat. After their first meeting Bridgeman noted that in Nightingale she ‘had an ambitious woman to deal with on whom she could not rely’. Furious with the British War Office for sending more nurses without consulting her, Nightingale rejected the new group as not wanted and not needed. Nightingale wanted to break up the group of fifteen nuns but Bridgeman was having none of it – she made it clear that she was in charge of her nursing party.

In the end, the Irish nuns did not trust Florence Nightingale. They believed she was ‘ever ready to receive complaints (or to imagine them) against the Sisters’. Nightingale’s dealings with the Irish Sisters were tinged by racism. She referred to Bridgeman as ‘Mother Brickbat’. In November 1855 in a letter to Lady Elizabeth Herbert she wrote (forgetting that her great supporter Clare Moore was also Irish), ‘It is the same old story. Ever since the days of Queen Elizabeth the chafing against secular supremacy, especially English, on the part of the R[oman] Catholic Irish … These Irish nuns are dead set against us … The proportion of R[oman] Catholics and of the Irish has increased considerably in the army since the last recruits. Had we more nuns, it would be very desirable, to diminish disaffection. But not just Irish ones.’

However, where it mattered was on the ground and the Irish nuns won the respect of all soldiers, regardless of creed, by their hard work and professionalism. Orderlies had been trying to treat the sick but had killed more than they cured. The sisters began to organize the hospital, clearing the beds of dead, nursing the cholera victims and bandaging the wounded. They stayed in the wards for twenty-four hours a day at first and then grabbed only a couple of hours rest each night. The Sisters cleaned up the hospital and the wounded, spoon-fed the very ill and tried to bring discipline among the orderlies who were drunk most of the time ‘to try to forget the horrible sights’. They sought out the Catholics who appeared to be in danger of death and took their names so that the overworked Catholic chaplains might go to them immediately. The very air was putrid with the smell of death. Those who died were placed in shallow graves covered in canvas and blankets as there were no coffins available. Through this charnel house moved the Irish Sisters, angels of mercy in their dark habits, cheerful, kind and never-tiring.

Among the wounded were many Irish servicemen who called out in their pain for ‘our own Sisters from Ireland’. From October 1855 to April 1856 the Irish nuns were stationed at the General Hospital, Balaclava, in the Crimea. Cholera broke out to add to the horror. Sr. Winifred, of Liverpool, collapsed on her feet beside Sr. Doyle and died twelve hours later. The majority of the nun’s cases were not wounded, but were men who had fallen ill or were suffering from the effects of the severe weather. Sr. Doyle described the cases of frostbite they had to treat:

The men who came from the Front had only thin linen suits – no other clothing to keep out the Crimean frost of 1854/55. When they were carried in on stretchers, their clothes had to be cut off. In most cases the flesh and the clothes were frozen together, and as for the feet, the boots had to be cut off bit by bit, the flesh coming off with them. Many pieces of flesh I have seen remaining in the boots.

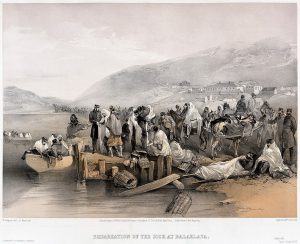

A tinted lithograph by William Simpson illustrating conditions of the sick and injured in Balaclava.

The Crimean War remains one of the blackest periods in the history of the British army’s medical services: 2,755 men were killed in action, while a further 2,019 died of wounds; disease claimed more than the fighting with 16,323 deaths. (Two of the Sisters of Mercy, Sr. Winifred Spry and Sr. Mary Butler, died in the Crimea.) The vital importance of the Sisters of Mercy’s careful nursing system was not lost on Florence Nightingale. She took it up as her own and their structure became the foundation for the development of modern nursing.

In February 1856 negotiations began in Paris to end the senseless conflict. The Treaty of Paris, signed on 30 March 1856, ended the war with an Allied victory and the surrender by Russia of most of the territory it had annexed. With the ending of the war the Sisters made their return to Ireland from Constantinople on the steam transport Cleopatra. The Turkish Sultan, Abdul Medged, sent a gift of £230 to the Sisters of Mercy in recognition of their services. On 13 May 1856 the Cleopatra docked in Spithead, Hampshire, with ten Irish Sisters of Mercy along with the Catholic chaplain J. T. Woolett onboard. When the Sisters returned home to Ireland great crowds gathered to cheer the ‘Russian Nuns’ and a Solemn High Mass with Te Deum was celebrated in Carlow Cathedral.

After her return from the Crimea Sr. Doyle led a foundation of the Sisters of Mercy to Gort, Co. Galway, in 1857. Sr. Mary Aloysius was appointed Superioress of the Gort Foundation and opened a school there two years later. From that foundation other convents were established. Mother Aloysius acquired a site at Ennistymon, Co. Clare, where on 19 July 1874 the foundation stone of Mount St. Joseph’s Convent was laid by His Lordship Most Rev. Dr. McEvilly, Lord Bishop of Galway and Kilfenora, under the patronage of St. Joseph. In 1878, a new foundation was opened at Kinvara, Co. Galway, where Mother Aloysius spent much of her later life.

On the occasion of Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee in 1897 Mother Aloysius, the only surviving Irish Crimean War nurse, was invited to Windsor Palace to accept the Royal Red Cross. Due to her age and infirmity she reluctantly declined to travel but accepted the Order of the Red Cross ‘the Queen is pleased to bestow on me’. Mother Aloysius celebrated the Golden Jubilee of her profession on 28 December 1901. She was prevailed on to record her experiences in the Crimea which was published in 1904 although some of her notes had been eaten by rats during the war. Mother M. Aloysius Doyle died on 3 October 1908 ‘a very old lady but quite lucid in her mind’.