A PANDEMIC RELECTION

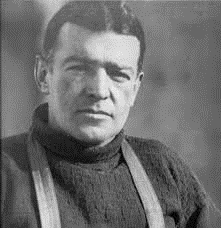

Liam Kenny reflects on how the Covid19 virus has stricken community life in Kildare and draws inspiration from the virtues of polar explorer Sir Ernest Shackleton

A pandemic reflection …

No Punchestown. No Bodenstown. No Kildare Derby Festival. No Athy County Show. No Community Games. No Tidy Towns. No - or very circumscribed - communion, confirmation and christening celebrations.

The litany of family and communal rituals suppressed by the dreadful corona virus is a stark reminder of how the pandemic has shredded the staples of Kildare’s community and social life.

From Celbridge to Castledermot and from Rathmore to Rathangan, the big days that mark the passing of the year in town and parish have been blown off the calendar by this menacing intruder.

At the beginning of 2020 none could have envisaged that an organism so small that it cannot be seen with the naked eye, could bring an uncompromising halt to the progress and gaiety of the county. Yet that is what we as a society have been faced with and, at time of writing, there is no knowing of how long the virus’s malign influence will persist.

The reckoning from this public health emergency will be long and hard. In commercial terms it does not take economic genius to survey the closed shops in the high streets of our towns and to assess the carnage unfolding in the myriad of background wholesalers and distributors.

True, it has been a tale of two economies. Some sectors including construction, technology and supermarket-retail have done well, boosted by the cash saved by those workers who found themselves freed from commuting costs while working from home. It is indicative of a pandemic bonus for some that the only new outlets to open in the county town as the lockdown tightened were home-furnishing shops.

However, for a multitude of other business people the year has been catastrophic. The array of small shops, travel agents, barbers, boutiques, pubs, restaurants and cafes which have had to shutter for months has seen the once-thronged pavements of our towns become like a scene from a dystopian film where little moves except the odd urban fox roaming the near-deserted streets.

Not alone do these businesses and their staffs represent the beating heart of towns and villages they are also social spaces in the community where people chat, connect and converse.

Factor in too the suspension of scores of clubs, societies, and committees which make things work in our localities and which provide an essential outlet and diversion for people,young and old. Take, as just one example, the three “B’s” - bingo, bridge, and bowls - which keep thousands entertained during the long winter nights. All have had to bar their doors leaving their loyal patrons with nowhere to go other than to stare at the four walls of their domestic spaces.

For homebirds it probably meant little change but for those invested in their communities, the pandemic has brought impacts of isolation and bewilderment. The toll on physical and psychological health is deeply rooted and the stories of quiet despair will fill many a consulting room for months to come.

In terms of religious practice, the change has been equally transformative. Not even in Ireland’s darkest days of revolution and war were the churches closed. Yet all denominations now see celebrants ministering to empty pews. For Catholics, for whom weekly Mass attendance is a source of spiritual and social connection, all has changed. The transition from real ceremonies to online Mass has helped fill the devotional chasm but the change has been nothing less than a Vatican III in terms of its implications for the concept of church as a worshipping community.

So in the face of such overwhelming circumstances can any inspiration be found? Is there an example where the much-quoted value of “resilience” is evident and that can be adapted to modern times to help our society tolerate the punishing circumstances of the pandemic?

Perhaps a thread of inspiration can be drawn from relatively close to home – from the legacy of the Kildare-born polar explorer Sir Ernest Shackleton (1874-1922). Born into a long-established Quaker family at Kilkea House, between Athy and

Castledermot, Shackleton went to England as an adolescent where he joined the harsh ranks of the merchant navy. Soon his aptitude for leadership was noticed by higher authorities and he was offered a place on a prestigious exploration expedition – a voyage to the distant southern oceans to explore and map the Antarctic continent with the ultimate prize of reaching the South Pole, the one frontier yet to be conquered by man.

On arrival in the deep southern latitudes, Shackleton fell under the spell of the frozen continent which, despite the harshness of its environment, he found mesmerising in its elemental ice-bound beauty.

As his Antarctic experience mounted through repeated voyages south he went from being a participant in polar expeditions to being a leader. He never reached the South Pole – although he came close – but he led men exploring and mapping vast tracts of the polar icesheets in a series of daring expeditions which set new records for endurance.

But it was his leadership in the face of adversity which has given him a permanent place in the textbooks on motivation and management. His responsibility was great and immediate. The conditions on the Antarctic ice cap were merciless. A man’s exposed skin would turn raw with frostbite within minutes while his shoulders chafed with the strain of ropes as he man-hauled laden sledges across expanses of corrugated ice. There were no creature comforts on the frozen continent. Everything including food and fuel had to be dragged – mostly by manpower – from one supply depot to another.

Even the most well-planned expedition could be visited by calamity within hours as the polar climate unleashed its raw ferocity.

And so it proved for Shackleton’s 1914 expedition originated by himself on board his ship Endurance. Attempting to navigate a route between the ice floes ever deeper into the continent, the ship became trapped in a frozen channel. For ten months Shackleton and his men could only look on as the relentless ice pack battered and buckled even the strongest ship’s timbers.

Eventually the vessel disintegrated into the ice leaving Shackleton and crew isolated with the nearest help many hundreds of miles away. It was a time when men could easily surrender to dissension and despair. However, Shackleton’s attributes of leadership and resilience came to the fore and, leading by example, he worked to make their emergency camp as comfortable as possible in the face of the ferocious conditions. But more needed to be done, their food would not last forever and some way of getting help needed to be found.

A consummate judge of character Shackleton selected a crisis crew of six from the larger crew of twenty-eight from the Endurance. With this chosen crew he manned a small lifeboat which had been saved from the larger vessel before it went down.

After an anxious farewell to their shipmates this small crew set out into the roiling seas of the Antarctic ocean to try and reach civilisation. The fate of their comrades left behind on a bleak icebound island rested with them. Their little lifeboat was tossed like a toy as mountainous walls of water cascaded on all sides. Keeping the boat on its heading not to mind navigating by the stars across eight hundred miles of ocean took all their strength and skill.

Yet in one of the all-time great feats of marine navigation, Shackleton managed to steer the boat to the tiny island of South Georgia where an incredulous Norwegian whaler was the first other human they had seen in eighteen months. Three attempts to rescue the 22 men who remained back at the site of the shipwreck failed due to the ice conditions. Eventually, after he pleaded with the Chilean authorities identifying himself explicitly as an ‘Irish explorer’, a ship and crew were supplied and a rescue expedition set out to retrieve the crew of the Endurance. Incredibly, none had succumbed to the cold and all eventually found their way to their far-away homes in the northern hemisphere.

Prior to the Endurance expedition, Shackleton had been asked to write an insight into how he managed to maintain his own morale and that of his crews when faced with seemingly overwhelming odds on his polar expeditions. After some reflection he put down in his own words the four characteristics which were his personal resources in the face of adversity:

- “Optimism: – To be cheerful when one gets out of one’s sleeping-bag into forty degrees below zero, and to feel that, however cold it might be, it might be colder. To realise that the goal that is many hundreds of miles away is in existence, and it only needs endeavour to get there;

- Patience: – Hardly ever have I seen a day begin well that has not had its difficulties demanding endless patience. A blizzard may spring up and for five days at a stretch our party may have had to lie in their cold sleeping bags. Then is the time to be patient, and the patience is rewarded; the storm ceases and the sun shines. Again, the same thing occurs in daily life. In business there are difficulties requiring patience. At home there are troubles requiring the same quality. Indeed, the quality of patience holds good whether at home or far away.

- Idealism: – Idealism and imagination allow one to feel that troubles and difficulties are made to be overcome.

- Courage: courage is never needed more than it is in the polar regions, for there one’s enemy is nature. But also, in the teeming city or in the farm and all the daily walks of life, courage is required to test the difficulties that arise from temptations to taking the rose-leaf path.”

The situation faced by the people of Kildare in this fraught mid-winter with an evil virus casting its shadow over our lives is one in which demoralisation could easily prevail. However, if we were to revisit the hard-earned wisdom of our fellow county-man, Sir Ernest Shackleton, and draw on his faith in the virtues of optimism, patience, idealism and courage, we might well find encouraging foundations on which to ground hopes for a better future.

A podcast ‘What would Shackleton do?’ is available free of charge on most podcast channels including Spotify and iTunes, or from the Shackleton Museum at https://shackletonmuseum.com/audio-visual/. My gratitude to the Athy Shackleton Museum Committee for inspiring this article.

Published in Leinster Leader Annual 2020