THE LADY NELSON. SHIPWRECKED 14 OCTOBER 1849. AN UPDATE

The Lady Nelson – Shipwrecked 14 October 1809

An Update

James Robinson, M.Phil.

In 2012, I published a paper on the loss of the Lady Nelson. In the intervening years, further information on this ship has come to light, which has prompted me to update my original publication.

There are approximately 900 shipwrecks off the Kerry coast. On Christmas Day 2020, a two-hour programme on some of these wreckages, which included the Lady Nelson, was broadcast on Radio Kerry.

This, then, is an update on my original paper.

On October 14 1809, the Lady Nelson, Captain Bernard Wade, was shipwrecked on a voyage from Oporto to Liverpool, off the Skelligs, Co. Kerry. The 200 tonne vessel contained a cargo of wine and fruit. 25 souls perished in the disaster.

The Freeman’s Journal of October 25 1809 reported the tragedy thus:

A further report in the same newspaper of the following day gave additional details of the shipwreck:

Several casks of wine have within the last week been thrown ashore and picked up by boats on the western coast of the county Kerry – a part of the wreck of a vessel was also discovered by a boat of Mr. Rice’s, and brought to Dingle; on which were found the captain, his wife and child, and maid-servant, quite dead, and two men, part of the crew, nearly in the same state; the latter, however, by proper care and attention, are now perfectly restored. From these men (one of whom is a Swede and the other an Italian) it has been learned, that the vessel was the Lady Nelson of Dublin, Captain Wade, from Oporto to Liverpool, dashed to pieces on Saturday 14th inst. on the Lecon Rocks, between the Skellix and the Main Land, and that her crew consisted of 22 sailors, one man, two women, and a child, passengers, all of whom perished except themselves, who were four days and nights exposed to hunger in the wreck before they were taken up. The cargo of the Lady Nelson consisted of 450 pipes of port wine, 12 of which were driven on shore at Valentia and secured by Mr. Berill, Surveyor of the Port.

This report differs from the first in that it listed two women as passengers instead of three. The gentleman passenger referred to in the report of October 25 was identified by the following report in the Examiner of London, dated October 24 1809, ‘Lord St. Asaph it is said has received confirmation of the loss of the Lady Nelson of Liverpool. All on board perished including his Lordship’s son – an officer of the Coldstream Guards’.

This victim was Ensign the Hon. John Ashburnham, (born June 3 1789) whose family seat was Ashburnham Palace Sussex in England. I surmise that this young man had served in the British Army, in the Napoleonic Wars and that he perished while returning home from Portugal. He was the fourth child of George, 3rd Earl of Ashburnham (styled Viscount St. Asaph from birth) and his first wife Thynn, daughter of 3rd Viscount Weymouth. Unfortunately for him, George Ashburnham chose to return home on the Lady Nelson. He was 20 years of age.

Lloyds Marine Register dated October 29 1809, referred to the tragedy with the following entry: ‘The Lady Nelson, Wade from Oporto to Liverpool, was totally lost near the Skelligs coast of Ireland 14th inst. Only 2 of the crew saved.’

The Public Ledger and Daily Advertiser issue of 12th September 1809 contained the following short notice.

Arrived

At Oporto, The Lady Nelson, Wade

This notice announced the arrival of the Lady Nelson in Oporto prior to picking up its cargo of wine and fruit, in advance of its final fateful voyage.

Another maritime website referred to the Lady Nelson as a full Rigger, 201 tonnes. It listed its cargo as wine, fruit and guns. The latter were 6 x 6 pounder and 4 x 12 pounder carronades. The full Rigger is a sailing vessel with three or more masts – all of them square rigged. The carronade was a short smooth bore iron cannon which was developed for the Royal Navy by the Carron Company, an iron works in Falkirk, Scotland. Used from the 1770s to 1850s, this cannon’s main function was to serve as a powerful, short range, anti-ship and anti-crew weapon. It was also used in the American Civil War in the 1860s.

This was not the first venture by The Lady Nelson to the Kerry coast. In January 1808, the year prior to its fatal final passage, this ship undertook a similar voyage. The Saunders Newsletter issue of 26th January 1808 reported that:

The brig Lady Nelson, Master Bernard Wade, from Oporto, with a cargo of wine & cc arrived at Limerick on Thursday last; on the preceding Saturday, when off the Blaskets, she was hailed by a large armed schooner, full of men, supposed to be a French privateer, who fired two shots at the Lady Nelson. But the latter having eight carriage guns, returned a full broadside, with full effect and that she had the pleasure of seeing the privateer run onshore.

This venture, together with its final voyage, also from Oporto to Liverpool, suggests that this was an annual trade route for the Lady Nelson. The intrepid nature of merchant sea travel in this era is well illustrated by this newspaper report. The good fortune to evade capture and destruction on this occasion was not replicated in the following year, 1809, when, on the same voyage, The Lady Nelson met her doom.

Samuel Kelly, in his book, referenced later in this paper, told of one Thomas Williams.

In March 1804, he, a mere boy, was captured by a French privateer. In May 1814, he was released, having spent ten years in various jails and marched over 3,000 miles in chains – 10 years of dungeons, rags and semi-starvation.

It was a risk that all merchant seamen in this era faced. Probably, not for the first time, The Lady Nelson had a lucky escape.

Earliest mention of the Lady Nelson in the Lloyd Registers is found for 1802. The ship (net tonnage 200 tonnes) was listed as being owned by Scott and Co. and the captain was named as D. Beck. Its trade route was given as plying between Greenock (Scotland) and Newfoundland (Canada). This report also stated that the ship had been captured as a prize. The Act of Union treaty of 1707 effected the union of Scotland and England under the name of Great Britain. Subsequent to this, Greenock became the main port on the west coast of Scotland. It prospered due to trade with the Americas, importing sugar from the Caribbean.

In 1803, the Lady Nelson was listed with the same ownership as the previous year and with R. McAlister succeeding D. Beck as captain of the ship. The following year, 1804, the ship plied between Greenock and Lisbon (Portugal). For 1805, the Register detailed Crawford and Co. as the new owners with McAlister still named as captain. However, this year’s entry stated that the ship had ten guns and that it journeyed between Greenock and Newfoundland. For 1806, the Lady Nelson was captained by B. Wade and ownership passed to Shaw & Co. Based in Greenock, the vessel plied between Dublin and Oporto. For this year alone, the vessel is listed as a privateer. This type of vessel was an armed ship which was privately owned and manned. It was commissioned by governments to attack and capture enemy boats. This ship’s details remained unchanged for 1807. For 1808, the registers show unchanged ownership and captaincy with its trade routes being Dublin to Oporto and London to Brazil. For the fateful year of 1809, the Lady Nelson was listed as having undergone a thorough repair with the vessel being sheathed with copper over boards. As in the previous year, there was no change in ownership or captaincy. Its trade routes were again given as Dublin to Oporto and London to Brazil.

This latter trade route suggests that it was part of the Slave Trade Triangle. The transatlantic slave trade took place between the continents of Europe, Africa and America from 17th to 19th Century. It was so-called as it comprised three different voyages which formed a triangular trade pattern.

Firstly from Europe to Africa, European slave-traders, including the British, bought enslaved Africans, which they exchanged for goods. These goods, such as cloth, guns, tools and alcohol, were shipped from European ports including London, Bristol and Liverpool.

The second leg of the slave trade was called the Middle Passage and involved the shipment of slaves from Africa to the Americas. Those who survived the brutal journey were sold as slaves to work on plantations.

The third part of the triangle involved the return from the Americas to Europe of plantation goods. These products included coffee, tobacco, rice and later cotton, which were brought to European ports, including Liverpool.

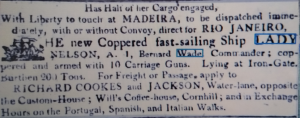

Evidence of The Lady Nelson’s trade route is shown by this advertisement in the Public Ledger – Daily Advertiser of London, issue of 1st July 1808.

Transcription:

Has Half of Her Cargo Engaged,

With Liberty to touch at Madeira, to be dispatched immediately, with or without Convoy, direct to RIO JANEIRO. The new Coppered fast sailing ship LADY NELSON, A.1, Bernard Wade Commander; coppered and armed with ten carriage guns. Lying at Iron.Gate, Burthen 200 tonnes. For Freight or Passage, apply to

RICHARD COOKES and JACKSON, Water-Lane, opposite the Custom House; Will’s Coffee-house, Cornhill; and in Exchange Hours on the Portugal, Spanish and Italian walks.

This advertisement requesting cargo and/or passengers showed a trade route to Brazil via a Madeira-stopover from London. The Madeira Islands are situated some 450kms. North of the Canary Islands off the coast of Africa.

The Lancaster Gazette issue of 27 May 1809 showed the Lady Nelson cargo on the return trip from Brazil to probably Liverpool.

Brazilia

Lady Nelson, B. Wade, from Rio Janeiro with 933 bales of Tallow, 2,893 dried hides, 11,158 horns, 45 sarons cotton, two cases of sugar, 50 bags coffee, five bales nutria skins, 50 quintals rosewood, 650 pieces do, two casks – case merchantize.

This advertisement informed purchasers and potential buyers of this merchandise in what turned out to be the Lady Nelson’s final trade voyage from Brazil to England. The nutria skins included in the cargo are a reference to a large rodent whose pelts were used in clothing manufacture. The rosewood reference is to a hardwood used in the manufacture of high-end furniture, which the better-off classes required.

The abolition of the British slave trade took place in February 1807, two years before the loss of the Lady Nelson. However, the slave trade continued for some years afterwards. It was finally abolished throughout the British Empire by an act of Parliament in 1833. At its peak, in 1799, it is estimated that ships from Liverpool carried over 45,000 slaves from Africa to the Americas.

While researching family history some twenty years ago, the writer was shown a small table which family tradition claimed came from a ship wreck. Further enquiries in other family branch lines in the same North Kildare area revealed an inscription written on the flyleaf of an old book. It read:

He was lost 14 Oct 1812

Bernard Wade Robinson

October 14th 1841 being

29 years after the loss

of the Lady Nelson and

of Captain Bernard Wade and

crew, which virry great loss

happened on that day

Bernard W Robinson

His namesake died on 16th May 1875

May the Lord have Mercy on their Souls

Bernard Wade Robinson (1818 – 1875)

‘May the Lord have Mercy on Their Souls’

The first line of entry was correct regarding the day and month, but wrong by three years (1809 instead of 1812) regarding the year of the tragedy.

The first two parts of the inscription were written by Bernard Wade Robinson (1818 – 1875) who was the nephew of Bernard Wade, Captain of the Lady Nelson. Bernard Wade’s sister, Johanna (1772 – 1863), married Garret Robinson (1773 – 1849) of Kilreany, Co. Kildare. This marriage took place on 14th February 1803 in St. Mary’s R.C. Church, now the Pro-Cathedral, Dublin. The witnesses were Margaret Gaynor and Elizabeth Daly. Garret was an emerging middleman/grazier who traded his farm produce in Dublin and possibly beyond. I surmise he met Bernard Wade and engaged in business with him regarding the sale of alcoholic beverages. Subsequently, Garret married Johanna Wade and their son Bernard wrote the above inscription which showed the impact of the shipwreck on the family.

The unpublished diaries of Garret Robinson record the sale of alcohol – a curious venture for a Co. Kildare farmer.

Watson’s Almanac lists Alexander Robinson as a merchant at 3 Fleet St. Dublin in 1789. Also, Ralph Shaw is listed as a merchant at 9 White’s Lane (now George’s Lane) in 1800. These are probably the same people referred to in Garret Robinson’s diaries.

Garret Robinson descended from Daniel McRobin (1690 – 1777) and his wife (née) Catherine Shaw (1696 – 1764), his grandparents and James McRobin (1734 – 1809) and his wife Ann (née) Shough (Shaw) (1744 – 1786), his parents. The family surname changed from McRobin to Robinson circa 1786. Members of this family also lived in Dublin at this time. Daniel McRobin/Robinson was a cooper and lived at 18a Thomas St. in 1789. Another possible kinsman was Daniel McRobin, who had a porter and chop- house on the corner of Dame St. and George’s Lane (now George’s St.) in 1778. It is noted that both were involved in the alcohol beverage industry.

Other possible maritime family connections were: in 1789 Robinson and Shaw ships brokers, 4 Bagnio Slip, Dublin; in 1772 Eleanor and James Robinson, ships brokers, 4 Bagnio Slip, Dublin and in 1782, James Robinson, ship broker, 2 Bagnio Slip. As Garret Robinson’s mother and grandmother were both named Shaw, it is possible that these families were connected. The Lady Nelson’s owner in 1809 was also named Shaw. The population of Dublin at this time was only about 180,000, making the probability of kinship of people of the same name far more likely.

I speculate that at some point in his business venture, Garret Robinson became involved in business with Bernard Wade, the captain of the Lady Nelson, and married his sister Johanna.

The former retailed the product (wine etc.) while the latter or his agent imported the goods. Prior to his association with the Lady Nelson, Bernard Wade was captain of a vessel named “Mary”, 165 tonnes, for the years 1804/1805. This ship was owned by Shaw & Co. (the same owners of the Lady Nelson) and it plied between Dublin and Oporto. Unfortunately, Lloyd’s Registers for 1802 and 1803 are missing. For 1801, the Mary’s captain was given as Scallan and it journeyed between Liverpool and Dublin. In 1799 its captaincy changed from Williams to Scallan with all other details unchanged.

The shipwreck of the Lady Nelson off the Kerry coast with a cargo of wine and fruit begs the question, was business (legal or otherwise) being conducted with Maurice ‘Hunting Cap’ O’Connell (1728 – 1825)? Maurice was the uncle of the Irish patriot, Daniel O’Connell (1775 – 1847), who was also known as the Liberator, due to his achievement of Catholic Emancipation in Ireland in 1829. Maurice controlled vast estates in Co. Kerry and had grown rich from smuggling. He amassed great fortune and achieved power and influence through his business activities. When charged with smuggling by Revenue Officer Whitwell Butler in 1782, O’Connell was able to ensure that the case was tried in Kerry. Not surprisingly, he was acquitted by a jury most probably composed of his own customers and associates. In a land lease to one of his tenants in 1793, Maurice O’Connell included the provision that ‘½ of all wrecks, lagans and salvages on said lands (in this case Ballinskelligs) to go to Thomas Segerson (his agent) provided the latter or his reps. assist in procuring and performing salvage’. In 1805, regarding correspondence with his uncle and benefactor, Daniel O’Connell noted, ‘A windfall of 40 barrels of brandy washed up from a wreck, on which the ‘old gentleman’ cleared £1,000…but not a word about that’. Daniel O’Connell inherited these estates on the death of his uncle in 1825.

The English county of Dorset has similarities to Kerry. Both are far from the control of central government and both had subsequently weak compliance with government laws in this era. Both are also maritime counties. Smuggling has long been important in Dorset and was tacitly approved of by most people, even the gentry. Thomas Hardy, the noted poet and novelist, wrote extensively of the struggles and striving of rural life in his native Dorset. It is said that Hardy’s grandfather had stored up to eighty tubs of brandy (each containing four gallons of smuggled brandy) in the cottage where Hardy was born. This made the whole house smell of spirits. Indeed, in Hardy’s mother’s time, an apparently very large woman would appear, asking if, “any of it were wanted cheap”. She carried smuggled spirits in bladders under her clothes. In Lyme, it was said that wise people stayed indoors when the phrase, ‘a white hare or rabbit about’ was used. It meant that a cargo of smuggled spirits had arrived and it was best not to notice.

A clergyman, Rev. S.G. Osbourne, suggested in 1849 that, “smuggling gave a large amount of employment to the peasantry of the county and directly and indirectly put a great deal of money in their way”. He added that its suppression was one of the causes of the poverty of the labourer in 19th century Dorset.

I believe that these sentiments resonate with Kerry inhabitants in this era also.

The term ‘pipe’ refers to a worm-shaped volume of 92 gallons. It was designed to suit transportation of wine on the River Douro to Oporto from inland Portugal. The cargo of the ill-fated Lady Nelson consisted of 450 pipes of wine. Garret Robinson’s diaries refer to his sale of similar wine volumes. The diaries also contain a page reserved for family birth and death details. This was filled in by succeeding generations of the family. A single-line entry recorded the tragedy: ‘Bernard Wade and his wife died 14th Oct 1809’.

There was no further alcohol sales recorded in the diaries after this date. Garret’s terse single-line entry recorded the end of a venture which must have caused great dismay, not to mention economic setback.

Garret Robinson became a substantial farmer in Co. Kildare and his will, made in 1849, contains the following, ‘My will and desire is that my said wife (Johanna) shall continue to reside in my dwelling house during her life with the same authority and command that she had during my life’.

This suggests that Johanna brought a substantial dowry to her marriage with Garret.

The loss of not alone her brother (Bernard), but also his wife and child, must have affected her and the family greatly. The Christian name Bernard subsequently became common in many branches of the Robinson family and testifies to the strong family resonance of the name.

Some thirty years after the loss of the Lady Nelson, Lady Chatterton recalled the saga as told by the survivors:

In the winter of 18– [sic] the Lady Nelson from Oporto to London (Liverpool?) laden with wine and fruit, struck on the large Skelligs and went to pieces. The mate had warned the captain during the evening of his proximity to this dangerous rock; but the captain, who was drunken and jealous, (his wife having seconded the representations of the mate), refused to put the vessel about and in a couple of hours she struck.

The mate and three hands saved themselves upon a part of the wreck, which was drifting about for three days, during which time they subsisted on the oranges and other fruit which, when the ships went to pieces, covered the sea around them. The mate, who was an excellent swimmer, procured these oranges by plunging off the spar and bringing them to his companions. On the third day, one man became delirious, saying that he should go ashore to dine. He threw himself off the spar and sank.

Shortly afterwards, the survivors were picked up by a fishing boat belonging to Dingle, which had come out looking for a wreck. The crew consisted of a father and his four sons, and had two pipes of wine in tow when they perceived the sufferers, finding their progress impeded by the casks and that the tide was sweeping the seamen into the breakers, where they must have been dashed to pieces, the old man nobly cut the tow line, abandoning what must have been a fortune to his family, and by great exertion picked the men up just when the delay of a second would have caused their destruction.

The Lady Nelson port is still famous in Kerry and a glass of it is sometimes offered as a ‘bon bouche’.

It is no wonder that the toast to the Lady Nelson was drunk after the tragedy, as only twelve pipes out of four hundred and fifty were recovered by customs.

This vivid story rivals anything written by Robert Louis Stevenson. All the ingredients for high drama are present: sex; alcohol; jealousy; anger; dangerous seas; loss of cargo, ship and life and not least, the saving of the survivors who were nobly rescued at the expense of the salvage, thus allowing this tale to be told.

Garret and Johanna Robinson are buried in Carrig cemetery near Edenderry, Co. Offaly with their son Bernard, who wrote the book inscription recalling the tragedy. The headstone inscription reads:

Sacred

To the memory of

Garret Robinson Esq.

Of

Kilreany

Who departed this life the 16th day of August

1849 aged 76 years

Also of his beloved wife

Johanna Robinson

Who departed this life on the 12th day of April

1863 aged 91 years

Also Bernard Wade Robinson

Who Departed this life on the 16th day of May

1875 aged 55 years

It is noted that the name Wade was incorporated into the family and it continues to this day in this branch of the Robinsons. A query to the Guildhall Library London regarding the Lady Nelson brought the response that the vessel was built in New York in 1799. The owner was Hunt and her usual voyage was between London and Brazil.

Family belief (so far unsubstantiated) is that Bernard Wade and his sister Johanna came from Liverpool. Garret Robinson’s diaries contain an inscription circa 1803 which supports this belief:

For Capt. Bernard Wade

To the care of Mssrs Jrdan (Jordan) of Liverpool

White House Merchant

The inscription is surrounded by a mass of financial calculations. Another diary entry dated September 1806 reads, ‘Cash lent Mrs. Eleanor Wade paid £6 – 16 – 6’.

Could this have been the wife of Bernard Wade and sister in law of Garret Robinson?

The fate of being shipwrecked almost befell Garret Robinson’s brother, Father John Robinson (1767 – 1822). Father John attended the Irish College Salamanca as a seminarian. His boat journey to Bilbao, en route to Salamanca, almost resulted in tragedy, as this letter to his father in 1787 details:

I am shure there was no one breathing has ever been attended with worse luck at sea than I. thanks be to God I am yet living which certainly is a great miracle for we have been three times cast on shore by the impetuous tempests that continually prevail. The wind was so favourable at the first going off In six days after we left London we got within fifteen leagues of Bilbao but a most sudden and terrible hurricane arising we were driven in less than twenty hours to Torbay a bay of the English Channel on the coast of Devonshire where we continued about two days when a favourable breese arising we put to sea again but with no better luck than before for we no longer got Clear of the rocks which are very numerous there than a tempest arising which drove us immediately back to Ireland but to what part of I certainly cannot tell for neither the Captain nor the pilot themselves know where we were only just to guess, the wind changing we were drove to France. So that now I may say I have been in England, Ireland, Isle of Man, and France and the much wished for Spain. Now I am safely arrived In Bilbao thanks be to God in good health though in a most feeble weak and emaciated condition but I hope with God’s assistance to be as strong as ever shortly for I have recovered vastly since I came onto the shore.

Father John Robinson was twenty years of age when this intrepid sea journey occurred, the same age as Ensign John Ashburnham who died on the Lady Nelson. The perilous nature of seafaring is evidenced by Edward Burke’s assertion that there were fifteen thousand shipwrecks estimated to have occurred off the Irish coast between 932 and 1997. Captain Bligh of ‘Bounty’ fame who surveyed Dublin Bay in 1800 acknowledged that terrible weather conditions contributed to that total. He also blamed the inexperience of masters and crews in many merchant ships as well as the meanness of many ship’s owners. The latter refused to pay for sufficient cable for ships anchors. He added that chain link cables would often snap due to inferior metal used in their construction.

In the case of the Lady Nelson, if Lady Chatterton is to be believed, it was marital infidelity which sealed the fate of the vessel, resulting in the loss of its cargo, including 41,400 gallons of wine. It is curious that Captain Wade had his wife and child on board the ship on this fateful business voyage. Perhaps it is fair to say that, if they had not been on board, the disaster would not have happened. Garret Robinson’s diary for 1801 valued the pipe of wine at £62. This indicates that the wine cargo of the Lady Nelson was worth about £28,000. This equates to a wine cargo value of about £2.25 million in today’s money. Tragically, 25 lives were lost in the disaster.

The Great Skellig by Richard Brydges Beechy

Probably the last scene visible to the terrified people on board the Lady Nelson on this fateful night was The Great Skellig. This dramatic painting, entitled, “The Great Skellig”, was executed in 1883 by Richard Brydges Beechey (1808 – 1895). Brydges Beechey was an Anglo-Irish painter and Admiral in the Royal Navy. Like his father and some of his brothers, he was a celebrated artist who illustrated various ports and naval scenes.

Samuel Kelly was the grandson of an army surgeon who had settled in Birr, Kings County, now Offaly. Kelly’s father was also a seaman. Samuel was born in June 1764 at St. Ives, Cornwall. In 1778, his first sea employment was on a packet bound for Madeira. Sea-sickness plagued him for weeks and when he landed at Madeira, the Captain permitted him to accompany him and the passengers on shore to view the town, which he found very pleasant and gratifying.

Here we landed a negro boy (Marcus) who Mr. Hall had purchased on the last voyage to the West Indies for Mr. Bell, the postmaster here, as a livery servant.

In 1781, while in Jamaica, he witnessed two seamen flogged for desertion, a most cruel punishment, especially as the desertions are sometimes occasioned by severe and cruel treatment.

The men were fixed to a kind of gallows in a boat and exposed to a tropical sun while going through their punishment.

He was informed that one of the men expired on the same day.

Also, in 1781, on another ship, the provisions were of infamous quality; the beef appeared coarse, the barrels of pork consisted of pigs’ heads with iron rings in their nose, pigs’ feet and pigs’ tails with much hair thereon. Each man had six pound of bread and five pounds of salted meat per week but neither beer or spirits were allowed.

In 1783, a ship on which he was employed was much-haunted with rats.

We therefore employed a rat-catcher from Portsmouth, who laid oatmeal balls containing poison in different parts of the vessel and on my going down in the afterhold two or three hours after it had been deposited, I heard a most pitiful outcry from members of these animals and killed one or two that were unable to escape from me. The stink from the dead in a little while was very disagreeable and I think we found some buckets full of rats amongst the cast, which we threw overboard.

In 1789, having been shipmaster of the JOHN, which sailed between Liverpool and Philadelphia, Samuel Kelly saw his wages rise to five pounds per month, having been three pounds per month while he was mate on his previous ship, THETSIS.

He went on to say that, during his whole time that he commanded a vessel (except his last voyage), that he never made more than 75 pounds per annum. He stated, “This was a miserable income for the duty, anxiety and responsibility of a shipmaster”.

In 1790, while in Philadelphia, Samuel Kelly attended at the door of the Senate to get a sight of the president (George Washington) on opening the Session.

I placed myself on the steps of the House. He soon afterwards arrived in an old coach, formally belonging to Governor Penn….. He wore black velvet with a silk bag on his hair and was so much like the picture of him that I had seen in England that I could easily have selected him from a thousand men. The Senate was well-crowded by the time I arrived at the top of the stairs but I got near the door to hear part of the speech and remained at the lower door when the President appeared again. He stood a minute on the steps to thank the police officers for their attendance and then dismissed them from further ceremony.

In 1792, while Kelly was in Malaga, an execution for murder occurred. The man was a convict in jail, where he quarreled with a fellow prisoner and killed him:

I waylaid the procession in the morning, having previously viewed the gallows on the beach. The criminal was drawn in a hurdle by an ass on which a man rode who was to be flogged. The sides of the matted hurdle were supported in the hands of the magistrates or other respectable men, fully dressed in black. A large concourse of ecclesiastics, police officers and troops were in the parade. After the whole had passed, I returned to my business, not being desirous to see the execution but towards 4 o’clock, my curiosity led me to the spot where I found the man hanging. The man was clothed in white flannel. Before him on the ground was a table on which a crucifix was placed, I think of silver, with lighted wax candles but whether the latter were intended to enlighted the sun or enliven the dead, I know not. I also understood that every shopkeeper was obliged to contribute towards his dress and every carpenter towards the gallows. That after condemnation his cell was hung with red cloth and everything that he desired to eat or drink was provided for him; cordials were also given to him by gentlemen to the place of execution. This condescension was a lesson of charity and contended to promote humility.

Also in 1792, Samuel Kelly landed for the first time in Ireland, where he docked his vessel, JOHN, in Newry. He went to the house of the merchant, the consignee of the cargo, where he was given a good dinner and a good bed for the night. After walking the town, Kelly returned to the house and reached in the pocket of his great coat for a handkerchief he had left there. Alas, it was gone and this assured him that there exists a thief, even in Ireland.

The town of Newry swarmed with beggars and he observed those lame, or placed on a hand-barrow and laid before the next neighbour’s door, who removed each person to the next house, either giving alms or not, and in this manner, the cripples were transported through the town… The lanes and highways were often crowded with emigrants for America, which was a far-from-pleasant sight.

In 1793, while in Bristol, Kelly observed a privateer, the BROTHERS, which sent in two prizes, captured ships, but they proved what seamen termed, ‘Flemish’. One was a Swede, which was soon liberated. The other, a Dane, with a French cargo for the West Indies, remained for the decision of the Court of Admiralty, which was finally liberated – a loss to the owners of the privateer of some thousands. The officers of the BROTHERS had wantonly tortured the Danish captain by means of a thumb-screw in hopes he would confess what nation owned his cargo, but they failed to obtain the desired information, leaving the owners of their ship open to the penalties of the law incurred by their bad conduct.

In 1794, while in Jamaica, Kelly found himself surrounded by slave ships from Africa, “The stench from which about daylight was intolerable and the noise through the day very unpleasant”. He therefore removed his ship to the windward and eastward of the nuisance.

These extracts from Samuel Kelly’s account of his first seventeen years at sea testify to an interesting and adventurous life. Bernard Wade left no account of his life at sea but it cannot be doubted that his maritime experiences were not dissimilar to that of Samuel Kelly. This was an era when England was at war with one power or another.

I have been unable to determine where Bernard Wade came from. A perusal of Wade family pedigrees from Westmeath and Meath do not show a connection to this mariner. As his sister Johanna was married in Dublin, it is possible that he came from there.

This episode from the Cromwellian colonisation of Ireland reveals a possible connection.

It was observed that many people were slipping into the country (Ireland) with arms and Irish privateers also became active against commonwealth shipping around the coast.

On 7th April 1656, Captain Henry Hatsell reported to Colonel John Clarke that his ship, the FRIENDSHIP out of Plymouth had been bound for Ireland with salt and deal timber when it had been attacked and taken off the Scilly Isles by Nicholas Hayes, an Irishman holding a commission from James, Duke of York, who put his quartermaster, Harry Wade and six other men, four being desperate Irishmen, into her with an order to carry her to St. Sebastian for condemnation. Wade appeared to have tired of the Royalists or have serving his captain for he sent two of his Irishmen under his command off to the nearest island in a boat on some errand and when they had gone, he ceased the other two Irishmen and had them bound. When the first two returned, he similarly bound them and put all four into a boat. He then freed Captain Hatsell and his crew.

Bernard Wade’s nephew, Edward Robinson (1814 – 1905) and his wife Bridget née Knight (1831 – 1906) of Kilrainey, Kildare, had a son, Harry and this Christian name persists to this day in this family. A life at sea was a profession that ran in families, as in Samuel Kelly’s case. It is possible that Bernard Wade descended from Harry Wade, who, some 200 years prior, had taken part in the Cromwellian wars. The name Harry reappeared as a consequence in his descendants. Edward Robinson’s branch of this family changed their name to Wade Robinson – a change which persists to this day.

The writer is a great-great-great-grandnephew of Bernard Wade. Most families have Christian names which recur in successive generations. He chose the name Bernard as his confirmation name without knowing its significance.

He does now.

Sources

- Freeman’s Journal, October 25 1809

- Freeman’s Journal, October 26 1809

- The Examiner, London, December 24 1809

- Lloyd’s Register of Shipping, www.Maritime Archives.co.uk/Registers.Aspx

- www.Irishshipwrecks.com

- www.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Ashburnham

- James Robinson, The Robinsons of North Kildare, McRobin Publications 1997

- Will No. T16704, Garret Robinson, National Archives, Dublin

- Lady Chatterton, Rambles in the South of Ireland Vol. 1, Published by Saunders & Otley, London, 1839

- John Watson, The Gentleman and Citizens Almanac, National Library, Ref. Ir01541:1

- The Dublin Evening Post, December 15 1778

- www.merseygateway.org

- http:abolition.e2hn(ornn).org/slavery

- www.h2g2.com

- www.wikipedia.org/wiki/greenock#early

- http://britannica.com

- Colin Sludds, The Building of Dun Laoghaire Harbour, Dublin Historical Record, Vol. LX1V, No. 1, Spring, 2011

- Edward Bourke, Shipwrecks of the Irish Coast 1993 – 1997, Vol. 2, ISPN 0952303711

- The Mammoth Book of Life Before the Mast, Edited by John E. Lewis, Robinson, London, 2001

- Http://Derrynane.com/Activities/Derrynane_House

- O’Connell Estate Papers, UCDA, Reference P-12-7 & P-12-A

- Http://Dictionary.reference.com/Browse/Privateer

- EN.Wikipedia.org/wiki/carronade

- www.IrishWrecksOnline.net

- Http://Salfalra.com/Other/Historical-UK-Inflation

- Charles Chenevix Trench, The Great Dan, Triad Grafton, 1986

- https://www.radiokerry.ie/podcasts/

- Saunders Newsletter, Tuesday 26th January 1808

- Public Ledger/Daily Advertiser, London, 1st July 1808

- The Lancaster Gazette, 27th May 1809

- The Public Ledger – Daily Advertiser, 12th September 1809

- R.C. Parish Registers, St. Mary’s, Pro-Cathedral, Dublin, 14th February 1803

- The Great Skellig, by Richard Brydges Beechy, The Maritime Museum of Ireland, Haigh Terrace, Dun Laoghaire

- Samuel Kelly, An 18th Century Seaman, Cornish Classics, 2005

- Hell or Connaught – The Cromwellian Colonisation of Ireland (1652 – 1660), Peter Beresford Ellis, P.178

- John Fowles, Jo Draper, Thomas Hardy’s England, Guild Publishing, London, 1984, Page 134. ISBN 0-224402974-6

I wish to thank all branches of the Robinson family who helped me in my research and in particular Colleen, who has been of invaluable assistance.

My sincere thanks go to the staff of the following institutions for their unfailing assistance and courtesy: The Royal Irish Academy; The National Library of Ireland; The National Archive and South Dublin County Libraries, Tallaght, Dublin 24 and the National Maritime Museum of Ireland.

Finally, my thanks go to my daughter June for her commendable wordsmith skills and never ending patience.