THE RATIFICATION OF THE TREATY 7 JANUARY 1922

100 years ago today

The ratification of the Treaty 7 January 1922

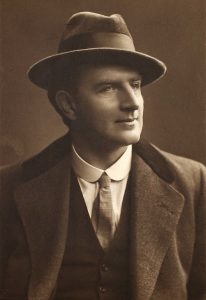

James Durney

Dáil Éireann met to debate the Anglo-Irish Treaty in the Council Chamber of UCD, then at Earlsfort Terrace (now the National Concert Hall), on 14 December 1921 for eight days and another five days in January. The debate broke for Christmas and renewed again in the new year. On 3 January 1922 the Dáil resumed the Treaty debate, while outside Earlsfort Terrace, crowds chanted ‘Ratify! Ratify!’ The first speaker was Kildare TD Art O’Connor who posed the question as to whether the Treaty was one of duress or consent. O’Connor, first elected as a Sinn Féin TD in the general election of 1918, spoke very eloquently:

‘I am going to try to set a good example at this renewed session of An Dáil by being very brief in what I have got to say …. I must say that the Treaty has suffered from its advocates both within this assembly and without it. I have been listening to the debates for several days and I have been unable to discover whether the Treaty is a Treaty by consent, or whether it is a Treaty signed under duress. To my mind it would make a big difference to this assembly if we knew definitely which was which – whether this assembly is being asked to go into the British Empire with its head up or whether it is being forced into the British Empire.’

After Art O’Connor quoted James Connolly when he said that it is not the extent of the step at all that matters, but it is the direction of the step, he was interrupted by Michael Collins who said to cheers from his supporters, ‘That’s the stuff. Hear, Hear. Good for Connolly.’ O’Connor then retorted, ‘Yes, you can applaud that because you think it suits your policy or is your policy. Yes, wrap as much of that soft soldier in as you possibly can because the result will prove that it is a step backward. It is a step off the solid rock. You are in the swamp, and you will be swamped.’ Collins replied that he ‘was often in a swamp and I did not get many to pull me out’, to which O’Connor said, ‘I would like to give you a long stick to pull you out, because I am sorry you are in it, and going into it.’

Asked by Seán Milroy, TD for Cavan and Fermanagh & Tyrone, what his constituents thought O’Connor replied,

‘… My constituents gave me a definite mandate in 1918, and they renewed that mandate last May. And my mandate was to the best of my ability I should support the Republican Government in this country. I have not changed. I told them they could change. Perhaps they have changed, but I will not change. I told them a couple of months ago when I spoke to them publicly that I would not change; they could change if they chose. I will vote against this Treaty because the acceptance of it would mean the death knell of this Dáil and Republic.’

The Treaty debate lasted to 7 January 1922 with many deep and moving speeches. However, it was a bad-tempered debate. Cathal Brugha mocked Collins’ stirring position as ‘the man who won the war’, while Constance Markievicz called Collins and his colleagues ‘oath breakers and cowards’. Collins in response labelled Éamon de Valera and Erskine Childers as ‘foreigners, Americans, English’ and their supporters as ‘deserters all to the Irish nation in her hour of need’. Before the final vote was taken de Valera uttered a last protest saying, ‘That document will rise in judgement against the men who say there’s only a shadow of difference’, while Michael Collins cried out, ‘Let the Irish nation judge us now and for future years.’ Then the vote was taken. Sixty-four voted for the Treaty while fifty-seven voted against, a majority of seven in favour of the Treaty. De Valera declared he would resign as Chief Executive and spoke of four years of ‘magnificent discipline in our nation’. Then as he said movingly, ‘The world is looking at us now…’ he broke down as tears overcame him.

The ratification of the Treaty was supported by the Catholic Church, local authorities and nearly every newspaper in the country, including the nationalist papers The Leinster Leader and The Nationalist & Leinster Times and the conservative Kildare Observer. Cardinal Michael Logue, Catholic primate of all Ireland, suggested that opponents of the Treaty did nothing ‘but talk and wrangle for days about their shadowy republic and their obligations to it’. The Kildare Observer noted in its editorial of 14 January 1922 that too much had been made of the people’s mandate for a Republic and the question of the Treaty and the establishment of an Irish Free State needed to be put before the people. In the end, it was the Irish people, for many reasons, who would give their greatest support to the ratification of the Treaty in the general election of June 1922.