The Truce. 11 July 1921.

The Truce

James Durney

A truce between the Irish Republican Army (IRA) and the British crown forces came into effect at twelve o’clock (noon) on Monday, 11 July 1921. The truce had been agreed on the Irish side by Éamon de Valera and Arthur Griffith and on the British side by General Neville Macready, General Officer Commanding British forces in Ireland. The War of Independence had caused 2,346 deaths, the majority after the arrival of the Black and Tans. While estimates vary, the figures for the breakdown of casualties from The Dead of the Irish Revolution (O’Halpin, E. & Ó Corráin, D.) – published 2020 – from 1917-21 are 919 civilians, 491 Irish republicans, 523 police, and 413 military.

By the summer of 1921 both sides in the conflict were beginning to contemplate peace. The war was costing Britain around £20 million annually, and, more importantly, the actions of the Black and Tans and Auxiliaries had become a great embarrassment. The IRA, too, was in some difficulty. It was running out of arms and was under pressure due to the imprisonment and death of many of its most experienced members. Both sides were anxious to end the conflict, and British Prime Minister Lloyd George invited de Valera, and any colleagues he should choose, to meet him in London.

Meanwhile, Arthur Griffith and several other prominent republicans, including Robert Barton, were released from jail. Delighted crowds cheered Gen. Nevil Macready to his meeting with Éamon de Valera, Cathal Brugha, Robert Barton and Eamon Duggan at Dublin’s Mansion House. The Earl of Middleton, St. John Broderick, a unionist with lands in Cork, acted as an intermediary with the approval of the British government. Discussions took place during the week beginning Monday, 4 July and the truce was officially announced on Friday, 8 July, to come into effect on the following Monday. The negotiations and the truce finally recognised the IRA as a combatant force, not a criminal gang; IRA Volunteers and Dáil TDs were to be safe from arrest or execution and there would be no surrender of IRA weapons as a precondition. The Dáil Publicity Department issued the following statement:

On behalf of the British Army it is agreed as follows:

- No incoming troops, RIC, and Auxiliary Police and munitions, and no movements for military purposes of troops and munitions, except maintenance drafts.

- No provocative display of forces, armed or unarmed.

- It is understood that all provisions of this truce apply to the martial law area equally with the rest of Ireland.

- No pursuit of Irish officers or men or war material or military stores.

- No secret agents, noting description or movements, and no interference, with the movements of Irish persons, military or civil, and no attempts to discover the haunts or habits of Irish officers and men.

Note:- This supposes the abandonment of Curfew restrictions.

- No pursuit or observance of lines of communication or connection.

Note:- there are other details connected with courts martial, motor permits, and ROIR to be agreed later.”

On behalf of the Irish Army it is agreed that:

- Attacks on Crown Forces and civilians to cease.

- No provocative displays of forces, armed or unarmed.

- No interference with Government or private property.

- To discountenance and prevent any action likely to cause disturbance of peace which might necessitate military interference.”

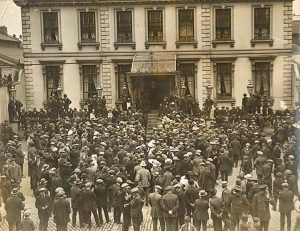

Crowds gather outside Dublin’s Mansion House on the day of the truce

Prior to the signing of the truce, on July 7, the Army and Navy Stores at Moorefield Road, Newbridge, was burnt down. IRA volunteers had sprinkled the goods with paraffin oil in order to render them useless. However, the owner William Doran, later came down to investigate holding a lighted candle. It was thought he let it fall and, in the resulting inferno his wife, Bridget Doran and their thirteen-year-old son, John, sleeping upstairs, were burned to death. Their funerals to St. Conleth’s Cemetery were held the day after the truce was announced. Rev. Fr. Kearney, C.C., speaking at the Masses in the parish church, said it was a consolation to know that the actual burning was accidental, but pouring out petrol in a place occupied by people seemed criminal.

Commandant Michael Smyth, who had been promoted to OC (Officer Commanding) 7th Brigade, 1st Eastern Division, IRA, on its formation the previous month, was arrested along with lieutenant of engineering, Bill Jones, near Two-Mile-House, on 7 July. Both men were armed, but they had time to throw their revolvers in a ditch; Jones had been on the run for some time. They were given a beating by Black and Tans, brought to Newbridge Barracks where they were held until 13 July, and then transferred to Hare Park Camp, the Curragh. Near Athy the trenching of roads continued up to the morning of the truce. Crown forces were active, too. The prominent IRA man Tom Behan, of Rathangan, was arrested on the morning of the truce and imprisoned in the Rath Internment Camp, the Curragh, where he remained until after the signing of the Treaty.

A general order issued from the 1st Eastern Division, IRA, to the headquarters of the 7th Brigade at Naas on 9 July said that although hostilities would cease in two days it was imperative that:

… a good stroke be made at the enemy before then. Such strokes will it is believed strengthen the hands of our representatives in the making of a definite peace. You will therefore hit anywhere and everywhere you can within your area before 12 noon on Monday. All spies of whom you may have already been advised of are to be executed also before said hour on Monday.

Thankfully, there was no appetite for more killing in Co. Kildare, and, despite the orders from HQ to keep the pressure up, there was little activity in the county. Peace prevailed and people in the county welcomed the coming truce. The Irish Times, of 11 July, reported: ‘The truce from warfare in Ireland will begin today at noon; but it was anticipated on Saturday and yesterday by the spirit of the truce. A walk in the streets of Dublin or in any country road revealed the immense satisfaction and relief which the good news had brought to all hearts. The very air held a new lightness and was irradiated not only with sunshine, but with hope …’

In Newbridge, Kildare, Athy and Monasterevin there were bonfires to celebrate the signing of the truce. Joyous crowds of singing people surrounded the bonfires. In Athy people were out strolling taking advantage of the relaxation of the curfew. That weekend the Leinster Leader reported: ‘The Armistice has been splendidly observed on all sides throughout Kildare. When in Celbridge one could see everyone on the point of extending congratulations and the same may be said all round. In Droichead Nua [Newbridge] and in Kildare areas there was a very good feeling shown and not the slightest matter occurred to mar the peaceful air which was evident the moment the entry of the peace had been made.’ The republican movement endeavoured to ensure that the conditions for the truce were observed, and they prohibited the singing of patriotic songs, especially after dark.

Truce liaison officers were appointed by both sides. Tom Lawler, from Halverstown Cross, Naas, who had succeeded Michael Smyth, as OC 7th Brigade, was appointed liaison officer with responsibility for North Kildare. Neither side believed the truce would last and both sides were using it as breathing space. In direct violation of the truce the IRA continued intelligence gathering, training, recruiting, and drilling, and was obviously preparing for a renewal of the conflict. The procurement of arms was stepped up; the famous Thompson sub-machine gun had arrived in Ireland in June 1921 and was used to effect in recent attacks. More ordnance was on its way, including two shipments of rifles, revolvers and ammunition from Germany. At the Curragh internment camps, prisoners continued with their escape bids; James Staines escaped on 19 August, while fifty-four men escaped through a tunnel in September – one of the escapees Liam Murphy later became a truce liaison officer in Kildare.

Comdt. Tom Lawler, Truce Liaison Officer, North Kildare

Shortly after the truce, the IRA secured an office in the Naas Town Hall and Republican police went on duty in the town. They began their work in a professional manner; for example, when two British lancers accosted a young female on the road from Sallins to Clane, they were arrested by the republican police and handed over to the IRA, who in turn handed them over to their regiment. During the War the two soldiers would probably have been shot out of hand. The monthly police report for July 1921 commented, ‘Since the Truce, the county has been very quiet,’ while for August it noted, ‘… the terms of the Truce have been very well observed by the rebels’.

However, with the dangerous times seemingly over many new recruits, derisively known as ‘trucers’ or ‘truciliers,’ flocked to the ranks of the IRA. Regardless, the IRA wanted to expand and were pleased with the opportunity to re-arm and re-train. In August the IRA established a training camp at Duckett’s Grove on the Carlow-Kildare county border, where Kildare IRA volunteers and Cumann na mBan members from the south of the county trained. Another training camp at Ballymacoll, Co. Meath, accommodated republicans from North Kildare. Within the county training camps were established at Dowdingstown House, Harristown House, Kildangan Castle and Celbridge Union. It looked like a return to war was inevitable.

The crown forces, too, were sceptical of the truce. There was a growing realisation of how elusive any long-term victory in the conflict would be. Despite suffering their highest casualties in the entire campaign between the start of May and the truce (48 fatalities), General Strickland, OC 6th Division, believed that the politicians had intervened just as the British Army was getting the upper hand over the IRA. General Jeudwine, OC 5th Division, scathingly said ‘the IRA leaders came out of their hiding places – convincing themselves and the population generally they had won the war’. Sir John Anderson, widely regarded as the ablest civil servant of his time, came to similar conclusions. He deduced that if the War restarted, it would have to be prosecuted on completely different lines, involving full martial law, economic blockade, and intense military occupation of a few strategic separate areas.

Meanwhile, the day after the truce came into being, an Irish peace delegation consisting of Éamon de Valera, Arthur Griffith, Austin Stack and Erskine Childers departed for London. Two days later they met Lloyd George in Downing Street to formulate the basis of what would become the treaty discussions. These negotiations would eventually lead to the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 6 December 1921 and subsequently a civil war.